YEVMYNKA AND LOST TIME

Sima Dehgani uses photographs to trace the history of the Ukrainian village of Yevminka. In 1943, almost all the village’s inhabitants were deported. Many were taken to Munich, some to Neuaubing. Most of them returned home after the war, but their lives were never the same again. Together with Kristina Tolok, an expert on Eastern Europe, she documents the stories and memories of contemporary witnesses and their families and the realities of their lives today.

It is green in Yevmynka. More than 500 people live here today; considerably more during the summer holidays. In July 2021 we traveled to the Ukrainian village to visit its inhabitants and their long-forgotten stories. Our small team consists of the photographer Sima Dehgani, Kristina Tolok, an expert on Eastern Europe and a staff member of the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism, and Liubov Danylenko, our Ukrainian translator. We left Kyiv in the morning. The journey took less than an hour.

Nina Tarasenko knows the route well. She travels by bus to Yevmynka every Sunday to take care of her mother’s house and garden. “The big garden is a lot of work. My children aren’t interested in it. But I can’t let it fall into neglect.” She left Yevmynka for the big city when she was a teenager and brought up her two daughters in Kyiv. Now she is approaching retirement. Not long ago her ninety-year-old mother Hanna Hutnyk came to live with her in Kyiv so that her daughter could take better care of her. Nina lives with her husband and her mother in a high-rise development on the edge of the city.

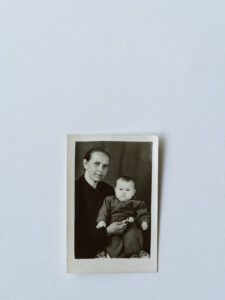

During World War II, at the age of thirteen, Hanna Hutnyk was deported together with her mother and five siblings to Hohenbrunn, near Munich. Her mother and her elder brothers Ivan, Volodymyr, and Fedir had to work as forced laborers for the army munitions facility (MUNA) in Hohenbrunn. Her two younger sisters, Agafia and Marina, did not survive the time in the camp; they died in Hohenbrunn at the ages of seven and three. Her father was drafted into the army at the beginning of the war and was never heard of again. After the war Hanna Hutnyk returned to Yevmynka together with her mother and three brothers. There she began working in the local Kolkhoz and had a daughter. “She built the house with her own hands, all by herself,” Nina Tarasenko says proudly of her mother. She also laid out the large garden. “My mother has always had green fingers.”

We drive through the village by car. The many traditional little wooden houses are now interspersed with larger vacation homes. There are also a large number of storks’ nests. We eventually arrive at the center of the village, where the school is. The summer holidays are comparatively long in Ukraine, lasting from June through August. In the playground we meet a group of children aged between ten and fourteen. Only one of the children goes to school here. Most of them are visiting their grandparents or great-grandparents. “Do they know anything about the war? What do they know about Germany?,” we ask. “I know that the Germans were here during the war,” says Vladik. “My great-grandma had to work in Germany.” A couple of phone calls later we’re sitting together with his mother, Yevgeniya Ovečko, in the house of his prababusya, his great-grandmother, Mariya Sadova. She is ninety-six years old.

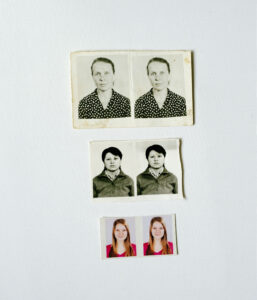

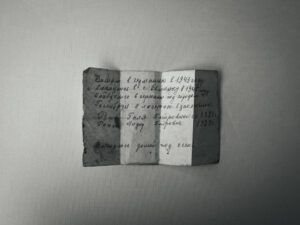

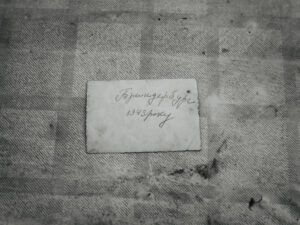

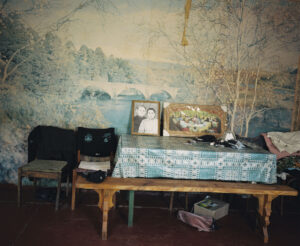

She was only seventeen when she was picked up alone in 1942. Her parents, Marfa und Fedir, and her three sisters, Valentina, Vera, and Halina, were deported the following year to perform forced labor in Germany. Like the Hutnyk family, they had to work for MUNA in Hohenbrunn. Mariya Sadova shows us old photos. On the back of one them “Branderburg, year 1943” is written in Ukrainian. She can no longer remember the name of the place or the company for which she had to work. “Opel,” says her granddaughter Yevgeniya Ovečko. “I grew up with these stories,” she explains. She comes to Yevmynka from Kyiv to visit her grandma as often as she can to help her with everyday chores.

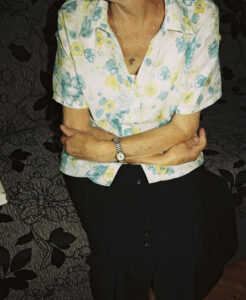

Oleksandra Havriš lives at the other end of the village. She is eighty-four years old. Her daughter Larisa Pisarenko welcomes us warmly to her parents’ house. She and another relative take care of her mother. Her father, Hryhoriy Havriš, died two years ago. He was chairman of the local kolkhoz representing the former forced laborers’ interests. He was the one who set up the contacts for the Munich Documentation Centre and led a team of historians through the village. Larisa Pisarenko speaks fondly of her father. “It’s hard, I miss him terribly,” she says. She works as a teacher in Yevmynka and takes care of her mother and mother-in-law in the village. Like her parents, her in-laws had to perform forced labor under the Nazis. Her mother on a farm near Munich, her father for a farmer in Mattsee in Austria. Both returned to Yevmynka after the war. They married and had two daughters.

The Nazi regime deported not only teenagers and adults but also children. A faded photo of a barracks shows just how many children there were. It belongs to Hanna Šust’. She is also from Yevmynka but now lives in Brovary, a suburb of Kyiv. She points to a little girl in the back row being carried by a woman with a white headscarf. “I was three years old there.” The photo was taken in the so-called “Eggarten-Lager”, one of the camps of the Reichsbahn Maintenance Workshops (RAW) in the Munich district of Freimann. She can’t remember how the photo came to be taken, nor who looked after her and her sister while her parents had to work.

Anna Šapovalova is also in the photo. Together with her parents and her older brother she was in the same camp as her friend Hanna Šust’. Now she is eighty-two. She invites us to coffee and cake in her Kyiv apartment. Awards and certificates attesting to her engagement for the former forced laborers hang in her living room. “I visit school classes and tell them about forced labor in Germany,” she says. Both women from Yevmynka have worked as volunteers for decades. When the first compensation payments were made in the 2000s, they helped many former Soviet forced laborers apply for them.

Both of them talk about the many difficulties and the bureaucracy involved in officially furnishing proof of their fates and stories. Photographs or objects from Germany may serve as evidence to support a compensation claim. But there are very few of them left, not least because during the Soviet era they could have caused difficulties for their owners. For the Soviet authorities those returning from Germany were under general suspicion of having worked voluntarily for the enemy and hence of having collaborated. Therefore, many people completely destroyed any evidence of their time as forced laborers. For a long time the subject was taboo and silence reigned. That has changed more recently. In Kyiv, on the site of Babyn Yar, there is now a central memorial commemorating the fate of the forced laborers.

Shortly before leaving Yevmynka, we get talking to Anatolii Vlasik by chance. He was born in Yevmynka and is now in his mid-forties. He’s been running a kiosk—the only store in the village—for a couple years. He tells us about his grandmother and her siblings, who were also deported to Germany. We talk about the village’s memorials to the veterans, partisans, and those who fell in World War II. “It’s a pity really,” Anatolii Vlasik admits: “They carted off half the village back then, but there is nothing here to remember those people.”

Text: Kristina Tolok