NAZI FORCED LABOR AND NEUAUBING

Forced labor as a mass crime

The former camp in Neuaubing is just one of an estimated 30,000 forced labor camps that existed throughout the German Reich during World War II. About 13.5 million people were deported from their countries of origin to toil under the Nazi regime. If we add to that figure all the people in the territories occupied by Nazi Germany who had to perform forced labor the total comes to more than 25 million. Despite the enormous scale of the Nazi system of forced labor, this crime plays only a relatively minor role in the collective memory today.

According to the historian Ulrich Herbert, Nazi forced labor is “the greatest example of the mass exploitation of foreign labor in history since the end of slavery in the nineteenth century.” The forced labor system was driven chiefly by the Nazi regime’s economic and military interests as the demand for armaments rose in the course of World War II. At the same time, the German economy was suffering an acute labor shortage on account of the many German men who had been drafted into the military. Without the use of forced laborers on a mass scale the Nazi regime could not have gone on waging war until 1945.

Forced laborers were employed in all sectors of the economy, ranging from armaments companies, to SMEs, the public service, for example in garbage disposal, or family-run farms.

For the most part, they were accommodated in the middle of German towns and villages. Some of them were housed in factory buildings or on company premises, others in specially built barracks complexes near their places of work or else in repurposed schools, gymnasiums, and guesthouses.

The Nazi administration allocated the forced laborers to different groups who were to be accommodated separately where possible, so those from the Soviet Union, for example, were put in different housing from the French or Belgian laborers, while the Poles were separated from the “Italian military internees.” The assignment to different groups was based on the Nazis’ racist idea that society should be divided along ethnic lines.

The forced laborers’ living conditions

Of the approximately 13.5 million forced laborers in Nazi Germany, more than 8 million of them were civilian forced laborers. These formed the largest group, followed by prisoners of war and concentration camp prisoners. Depending on their country of origin they were assigned a particular status determined by Nazi racial ideology. This affected their living and working conditions. The largest contingent of civilian forced laborers came from the Soviet Union and from Poland. Soviet forced laborers were known as “Ostarbeiter” (Eastern workers) under the Nazis. More than half of them were women whose average age was under twenty. But whole families, including many children and old people, were deported to perform forced labor, especially from Eastern Europe.

By contrast, the majority of forced laborers from Western Europe, from countries like the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, were male. Some of them initially came to Germany voluntarily, lured by the Nazi regime’s false promises, hoping for employment and decent wages. In reality, they often received hardly any wages at all and in many cases were not allowed to return home while the war was still on, despite provisions to the contrary in their work contracts.

Prisoners of war were also used as forced laborers in the German economy. Among them were 650,000 members of the Italian military who had between arrested following the collapse of the Hitler-Mussolini alliance in fall 1943. The majority of Soviet prisoners of war were murdered for racial reasons. Especially after 1944, concentration camp prisoners were set to work in the numerous subcamps and had to labor under appalling conditions, for example in quarries or mines.

More than 500,000 Germans were directly involved in organizing Nazi forced labor in various functions: as camp guards, in local employment offices which coordinated the “workforce requirements” of companies and the allocation of labor, or on the “recruitment committees” in the occupied territories, which were responsible for compulsory recruitment. The system known as the “deployment of foreigners” (“Ausländereinsatz”) became more professional over the years. As the scale of the war grew, the need for labor increased considerably. In 1942 a new administrative body was created headed by Fritz Sauckel, which was supposed to raise the efficiency of the system of exploitation.

The long wait for recognition

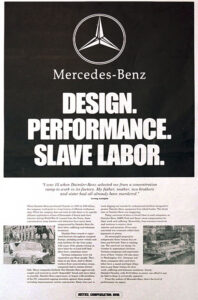

The mainstream society of Germany accepted the systematic exploitation and discrimination of millions of people as a necessary part of wartime life and as a rule did not question them. This scarcely changed even after the war was over. Although following the Nuremburg trials the facts about forced labor became common knowledge, this aspect of Nazi crimes soon disappeared from public discourse again and was largely ignored for decades.

Many of the forced laborers returned to their home countries after the war, but their experiences changed their lives forever. Their suffering was recognized only very belatedly, if at all. Very few of them received any compensation. On the contrary, in some countries they were for a long time regarded very critically and stigmatized for having “helped” the former enemy through their labor. In the Soviet Union, many former forced laborers remained under surveillance by the security services for decades.

Not until the year 2000 did the fate of the forced laborers receive more public attention. Pushed by the collective court cases brought against German companies in the United States, the Federal Republic of Germany decided to grant some kind of material acknowledgment after all. Via the then founded Foundation “Memory, Responsibility, Future” (EVZ), and numerous partner institutions in the home countries of the former forced laborers, a total of 4.4 billion euros were paid out to 1.6 million “eligible persons” in more than ninety states worldwide. Soviet prisoners of war received a symbolic recognition only later, in 2015. The “Italian military internees” have not been granted any kind of recognition or compensation to this day.

A place and its history: the former camp in Neuaubing from 1942 until today

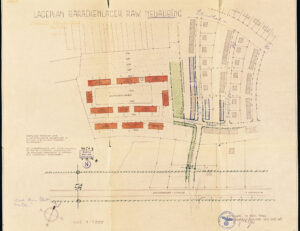

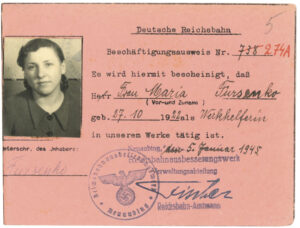

The barrack camp in Neuaubing was part of a dense network of more than 400 units of collective accommodation in the Munich area. Aubing and Neuaubing became part of the city of Munich in 1941 and formed a hub of Munich’s military industry. This was where many large companies relevant to the war were located, including the aircraft manufacturer Dornier-Werke and the German railways, the Reichsbahn. The Reichsbahn camp in Neuaubing housed up to 1,000 people, who worked at the maintenance workshops close by. These workshops were responsible for servicing, cleaning, and repairing railcars as well as for the production and installation of spare parts.

The barrack camp in Neuaubing was part of a dense network of more than 400 units of collective accommodation in the Munich area. Aubing and Neuaubing became part of the city of Munich in 1941 and formed a hub of Munich’s military industry. This was where many large companies relevant to the war were located, including the aircraft manufacturer Dornier-Werke and the German railways, the Reichsbahn. The Reichsbahn camp in Neuaubing housed up to 1,000 people, who worked at the maintenance workshops close by. These workshops were responsible for servicing, cleaning, and repairing railcars as well as for the production and installation of spare parts.

The camp, located on what is now Ehrenbürgstraße, was the largest of several housing units of the Reichsbahn in Neuaubing. It was opened in May 1942 and expanded in stages until 1945. The barracks housing the laborers had a planned capacity of more than 600 beds. In addition to these there were barracks assigned to various functions, such as kitchens, a sanitary facilities, and a guards’ barrack. Of the eleven planned barracks, nine were finished by the time the war ended; some of these differed from the original plans.

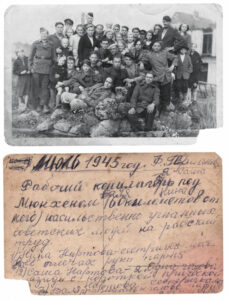

At the beginning the RAW camp accommodated exclusively civilian forced laborers from the Soviet Union. Later in the war people from other countries, including “Italian military internees” and Polish forced laborers were housed here as well. Probably in the last year of the war the camp was filled to, or even over capacity.

The camp was liberated by American forces on the morning of April 30, 1945. Many forced laborers remained in the vicinity for several weeks, waiting while the Allies organized their return home. After the last “Ostarbeiter” left in summer 1945, the camp was probably used for a short time to house German expellees and refugees. After 1949 the Deutsche Bundesbahn (the successor to the Reichsbahn) used the barracks as a hostel for its apprentices.

From the late 1970s onwards, the barracks were used by artisans and tradespeople, later also by a kindergarten and an animal farm for kids. The history of the place became overlaid by these new functions and was gradually forgotten by the public. Only around 2000 did it become the subject of a new focus as society’s engagement with the Nazi past grew and demands began to be made for compensation payments for former forced laborers.

At the same time, planning began for the new Munich district of Freiham. Inspections of adjacent areas once again brought to light their historical connections and ultimately led to a decision by the Munich city council in 2011 to establish a memorial site.

The remains of buildings where the mass crime of forced labor was perpetrated exist in only a few locations today. Thus as one of the last pieces of material testimony, the former camp in Neuaubing exemplifies the totalitarian system of Nazi forced labor and the systematic ostracization and exploitation of all those who did not conform with the Nazis’ ideological norms.

The new memorial site in Neuaubing will open in 2025. It is envisaged as a communicative space of remembrance that will facilitate a dialogue between the past, contemporary art and the local community about the history of Nazi forced labor, its current relevance, and its meaning for a pluralistic society in the present and future.

[1] Ulrich Herbert: Der „Ausländereinsatz” in der deutschen Kriegswirtschaft 1939-1945, in: Rimco Spanjer, Diete Oudesluijs, Johan Meijer (Hrsg.): Zur Arbeit gezwungen. Zwangsarbeit in Deutschland 1940-1945. Bremen 1999, S. 13-21, hier: S. 13.