MUNICH, MONACO, MALGOLO – and back

The forgotten stories of the “Italian military internees” or how a former forced laborer returned to the city where he was once exploited and invented a dessert that is still on German menus today.

Fotos: Alessandra Schellnegger

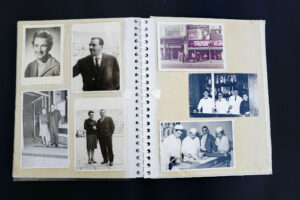

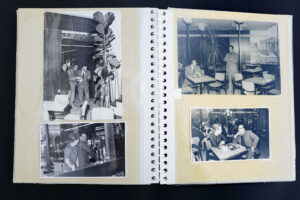

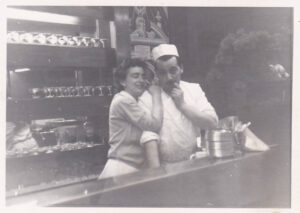

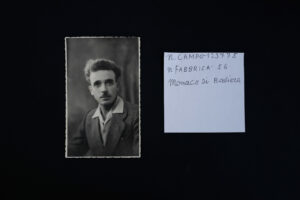

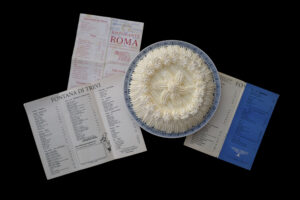

A summer in Monaco! How wonderful to spend two to three months selling cake and ice-cream on the promenade among the beautiful people—what could be nicer! It was a friend who drew Francesco Di Nuzzo’s attention to the position. Di Nuzzo, a young pastry cook from Naples, said yes straight away; he was often short of work over the summer after all. It was only when he came to buy a ticket that he realized he wasn’t going to the Côte d’Azur. His friend had got him a job not in Monte Carlo but in Munich—Monaco di Baviera. Francesco Di Nuzzo had already signed the contract so there was nothing for it but to spend the summer of 1952 in Germany, in the very city where only eight years earlier he had served as a forced laborer and been so malnourished that all his teeth had fallen out. That summer he spent the days serving a three-course menu to wealthy Munich citizens at the classy Ristorante Roma on Maximilianstraße; at night he was haunted by nightmares from Neuaubing.

Francesco di Nuzzo was one of 230, one of 150,000, or one of 13.5 million, depending on one’s perspective. 13.5 million people were abused as forced laborers under the Nazis. And that is actually a conservative estimate for the territory of the former German Reich. Other sources put the figure at 25 million if one includes the entire German Reich plus the occupied territories. Whatever the true figure is, it was certainly “the largest organized mass deportation campaign of all time.”

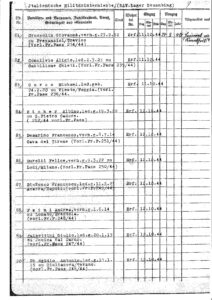

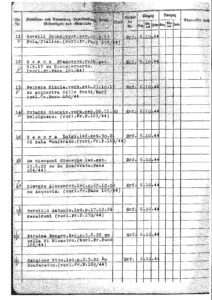

At least 150,000 foreigners had to perform forced labor in Munich alone. Today, we know for certain of 400 units of camp accommodation in the city region. The camps were everywhere, permanently visible to every German. Unlike the concentration camps, they were not located in secluded places away from the cities but in the middle of towns and communities, often close to arms factories or industrial enterprises. The French forced laborer François Cavanna wrote in his memoirs: “At that time Berlin was dotted with little wooden barracks. Rows of brown wooden huts with tarred roofing nestled into every space, no matter how small, throughout the huge city. Berlin was one giant camp.” In view of this it is really quite astonishing that today there are scarcely any traces left of this major chapter in the crimes of the Nazi era and only one official memorial site that has been made into a museum, the Nazi Forced Labor Documentation Center in Berlin-Schöneweide. The vast majority of the barracks have disappeared again without trace. In the whole of southern Germany only one ensemble has survived for decades: the eight barracks in Munich-Neuaubing, on the boundary to Freiham, that served as the camp for the German Railways maintenance workshops. Among those accommodated there were 230 Italian prisoners of war.

Thirty-seven kilos. That number keeps coming back. The ghost of Francesco Di Nuzzo looking like death on two legs haunts his four children as they tell his story. He weighed only thirty-seven kilos. All his teeth had fallen out. At the age of twenty-four. A shadow of his former self. During our conversation his children repeat these sentences many times, perhaps because they know so little and cling to the few facts they have. Francesco Di Nuzzo never talked to them about his time in Neuaubing. Prisoners of war were, after all, considered traitors, first in Germany, and then, after the war, back home in Italy too. And while the tales of the partisans grew into a heroic and inflated myth that formed the foundation for the new Italy, no-one wanted to know about the experiences of the up to 650,000 members of the military who had been exploited as forced laborers.

*

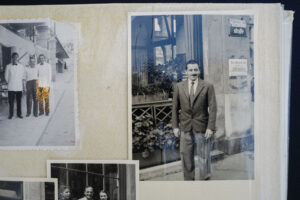

We’re sitting in the Nerina restaurant in Malgolo in Trentino. Outside, the October sun is bathing the trees in golden light. Inside the restaurant Di Nuzzo’s children have cooked a splendid meal for their German guests. Children? Well actually today they’re all between fifty and sixty years old. They were all born in Munich, thanks to the Monaco mix-up. Originally, he had planned to return home right away after finishing his summer job.

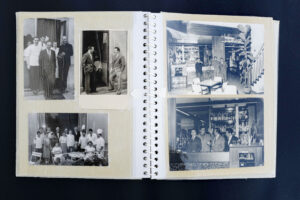

But then he met a very charming girl from Northern Italy at the Ristorante Roma and so he returned to Munich the following summer. He stayed fifteen years and opened his own restaurant, the “Fontana di Trevi” on Sonnenstraße. Every evening after the kitchen closed, he would distribute whatever was left over to needy fellow Italians at the back door. He and his wife had four children. They sent the two eldest to elementary school, where as foreigners they had to sit at the back of the class. “Until the first Turks arrived,” says Sandro, the eldest, as if that were simply a law of nature. “From that moment on we were only second last, and we were allowed to play with the others; now it was the Turks who were the outsiders.”

But what did their father do in Neuaubing? Ultimately, it was probably Neuaubing that killed him, that caused his missing teeth, bad heart, kidney failure. He died at the age of sixty-five. The children know that Francesco had to repair railway carriages, and they know that he had to clear debris while the bombs were raining down. They know of two anecdotes about appalling hunger and cold. But otherwise?

✽

In July 1943 at the latest, when Allied troops landed on Sicily, most of the nationalist-conservative Italian elite, who until then had been fascist sympathizers, turned their backs on fascism and Mussolini. King Victor Emanuel III had “il Duce” arrested on July 25 and installed Pietro Badoglio as the new prime minister. Only a few weeks later, on September 8, 1943, Badoglio announced Italy’s surrender.

Hitler, who had already condemned Mussolini’s fall as a “betrayal,” saw this surrender as yet another act of perfidious treachery. German propaganda raged against the Italians, claiming that they had already betrayed Germany in World War I so this was just yet another typically Italian move. This political stigmatization went down surprisingly well among the German population, so for the Germans the prisoners of war became a synonym for Italy’s “treachery” in changing sides. [3]

Ever since Mussolini’s removal the Wehrmacht had secretly been making plans for the event that Italy should surrender and had sent its own contingents to Italy, the Balkans, the south of France, and Greece. On September 8, 1943, most Italian units were taken completely by surprise by the announcement of the surrender. So in many cases the Wehrmacht didn’t have much trouble disarming the Italian troops. Often, they promised the Italian soldiers that they would take them back to Italy by train—if they would just relinquish their weapons they could go home right away. That was a lie of course. 25,000 Italian soldiers died during that time, either because they resisted being disarmed or because they were stuck on transport ships that were bombed or sank due to overloading.

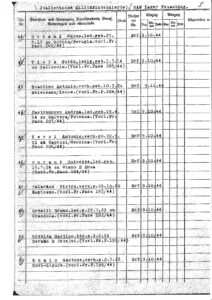

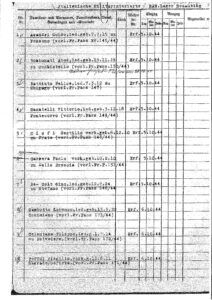

Instead, the trains took them to the German Reich, to the occupied territories in Poland, and to the Eastern Front. For the Germans it was a considerable gain in manpower. In total some 810,000 Italians fell into their hands. They were given a choice between continuing to fight on the German side or being taken prisoners of war. 650,000 men refused to collaborate and were sent to perform forced labor. Goebbels wrote in his diary that the “Italian treachery” had been a “good deal.” [4] For the Italians it was to be a traumatic experience. As punishment for their “betrayal” they found themselves at the bottom of the racial hierarchy working alongside forced laborers from the Soviet Union. That meant they received even more meager rations than French or Dutch forced laborers. Like the Soviet prisoners most of the Italians were subjected to the cruel principle of “performance-based nourishment”: anyone who did not fulfil their work allocation had their already meager ration taken away. Tens of thousands of laborers therefore found themselves in a “vicious circle of undernourishment, reduced performance, punishment, and further reduced food rations.” [5] No wonder that their memories are full of tales of eating scraps of food, of fried rats, of psychosis brought on by starvation, and of being spat at and beaten by the civilian population.

The Germans freed Mussolini and declared him the leader of the fascist Repubblica Sociale Italiana (RSI), a truncated state confined to Northern and Central Italy, which remained an ally of the German Reich until the end of the war. However, members of the military from an allied state could not be prisoners of war. For that reason Hitler changed their status at the end of September 1943 and declared them to be “Italian military internees” (IMIs). But there was another reason for giving them a different name: the Geneva Convention forbade the employment of prisoners of war in arms factories, but this ban did not apply to “military internees.”

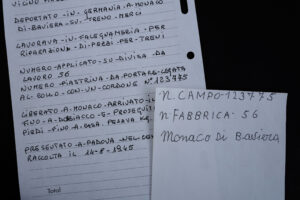

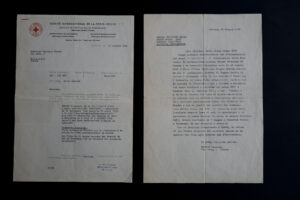

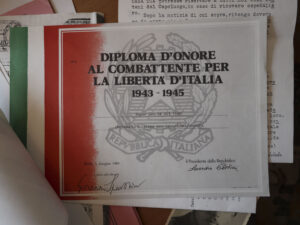

The Italians probably didn’t care what they were officially called; they had enough to do just trying to survive the harassment and food deprivation they were being subjected to while performing heavy physical labor. But later this designation was to prove fatal: Di Nuzzo’s children have a letter from the Italian government, a reply to his request for compensation. “Unfortunately, no”,” the government official wrote, he hadn’t been in a concentration camp after all. All the IMIs who asked for compensation received the same letter. None of them ever received any money from the Italian state (nor from the German state either for that matter, but more on this later). On the contrary, when they returned home, they were regarded by many Italians as collaborators who had helped the despised Germans hold out for longer.

✽

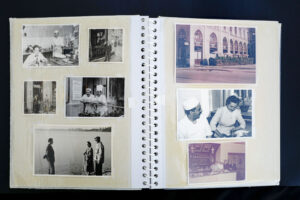

We visited the children of six former Italian forced laborers in Northern Italy in order to find out what their fathers had told them about their time in Neuaubing. It was a journey into a deafening silence—sixty- or seventy-year old men and women sitting there with a couple of documents and photocopies and a hole in their lives. All of them are in possession of a very similar letter rejecting their father’s request for compensation. Even the children still find this refusal to recognize their fathers’ suffering painful.

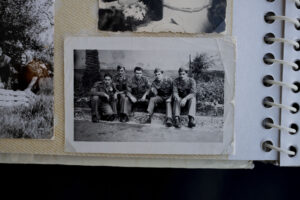

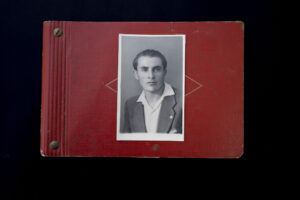

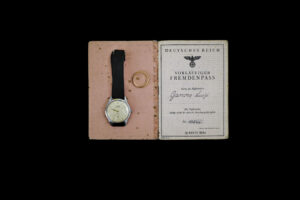

Pier Vanni Ganora lives in an apartment in Turin. He can recite all the figures pertaining to his father Luigi’s war experiences by heart: drafted on April 28, 1941, taken prisoner on September 15, 1943, returned home in June 1945. He stares at these few figures and photocopies but he knows nothing about the life that happened in between. Only that his father was beaten and mocked by Neuaubing children on his daily march to the railway carriages. That he later had an almost compulsive need to hoard bread. That he never wanted to return to Germany. And he cannot forgive himself for not having asked, for not having drawn his father out of his gloomy silence. Pier Vanni Ganora looks at the yellowing photos of his then twenty-four-year-old father in uniform staring back at his gray-haired son, until the latter begins to weep and shrugs his shoulders: “I don’t know anything. Nothing at all.”

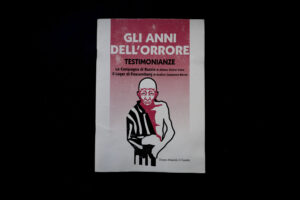

Fabia De Zolt receives us in her living room. Her father Gino died of COVID-19 last year at the age of ninety-six. Gino De Zolt spoke about his experiences in Germany only once, in 2017, when a historian from the Munich Documentation Center came to visit him here in Pieve di Cadore, at the foot of the Dolomites.

On that day Fabia sat down secretly next to the stove and wrote down what her father was telling the historian in the next room: about the women and children who spat in the Italians’ faces on their way to work. The hunger that plagued him every night. His hollow laugh when the historian asked him whether there was ever any meat to eat in Neuaubing. How he returned “thin as a rake.” When the historian asked him toward the end of the conversation whether he had at least talked to his brother who had likewise been somewhere in Germany as a “military internee” about this time, he said only “No, what for?” The next day Fabia tried once again to ask her father about Neuaubing, “but he said, he never wanted to talk about it again.” With her hand she makes a gesture like a guillotine. “Niente. Silenzio.”

Despite all the individual differences between our six encounters, one thing was very striking in all of them. Even if their fathers had always maintained a leaden or bitter silence about their experiences, they all knew something about the terrible hunger of that time. Alfredo Burani related how his father Giuseppe “later never left even a crumb on his plate.” Similarly Franco Degiovanni told us that for his father Giuseppe bread was always “sacred” in later years. Another strand that runs through all the conversations is the hurt suffered from never having received any recognition of their fates. Pier Vanni Ganora, for example, said his father Luigi was a very sociable, caring, philanthropic person, but he had locked away his time in Germany inside him, especially after the Italian state refused to grant him any recognition. Perhaps the most interesting moment in these encounters was the following: During the interview with Ganora his wife was present as well. Whereas Ganora clung to the meager couple of dates that he knew, his wife was almost chatty as she talked about her father. After having his weapons taken away by the Germans he was brought to a barracks yard where he experienced the same key scene: There a table was set and the Germans said: “Either you fight for Mussolini or you’ll go to Germany.” But he managed to escape and joined the partisans. After the war he liked to talk about it. She retell this story cheerfully, almost with pride. “Well,” says Pier Vanni Ganora after a long silence, “That’s a different story. It was easier to talk about that, everyone wanted to hear it.”

And then there are completely different stories, like that of Albino Eicher Clere, who was incredibly fortunate because some Party bigwig’s wife took his father Lucio in like a son, more or less adopted him: “The son of these Germans was fighting in the war down in Southern Italy. Maybe my father reminded her of her son; anyway, thanks to this woman he was well fed and he worked for the family in the garden and in the fields. He was totally privileged. ”

✽

Perhaps the 650,000 Italian internees who returned home would have talked more if they had ever received compensation. The Italian government could at least have recognized the fact that all the military internees chose hard forced labor over collaboration with SS units or the troops at Saló. It would no doubt be wrong to glorify this decision in all cases as “unarmed resistance,” since there was certainly not a broad antifascist consensus among the military internees. But the fact that their experience was completely erased from the collective memory drove many of them into an embittered silence, especially as the German government has never paid these 650,000 men a cent either; nor indeed have the German companies that profited so enormously from their labor. It could hardly be more cynical. During the war these men were treated worse than other prisoners of war, but in retrospect their suffering was denied.

The German Federal Indemnification Act, which came into force in 1953, applied to people who had been persecuted for racial, religious, or political reasons but excluded those who had been deported “only” to be exploited as forced laborers. In 2000 the Foundation Remembrance, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ) was founded. It received 50 percent of its funding from the federal government and 50 percent from private companies, although the companies were able to claim a tax break on their share. The EVZ negotiated payments for former laborers from various countries, but the Italian military internees and the Soviet prisoners of war were excluded. In 2015 the German federal government decided to make a final, purely symbolic “recognition payment” to the last former Soviet work slaves still alive. An expert report commissioned by the federal government came to the conclusion that the Italian military internees had in fact been prisoners of war the whole time and were therefore not entitled to any money. Historians such as Ulrich Herbert are sharply critical of this assessment, calling it a farce and a cheap legal trick, but this did not change the outcome: the Italian forced laborers were never compensated.

✽

The four Di Nuzzo children still run their parents’ restaurant today. Up here in the Trentino, Francesco opened a restaurant called Nerina and introduced Southern Italian cuisine. “Freshly made pasta was a new thing in Malgolo”, says Sandro. Even today the four children still use their father’s recipes. During our visit we too are wined and dined. To round off the meal Mario brings in a dessert that originated in Munich: during his time at Ristorante Roma, Francesco Di Nuzzo was one day asked to create his own dessert. Francesco took sponge cake, lashings of sherry, rum, water, and sugar and covered it all in cream and syrup. And so it happened that this man who had lived off potato peelings while performing forced labor on the outskirts of Munich and had lost all his teeth, ten years later invented Zuppa Romana for a restaurant in the wealthy heart of the city. Zuppa Romana can still be found on many Munich menus to this day.

✽

If the common European idea is to be credible, there must also be shared remembrance. Cultures of remembrance are nearly always nationally structured and separate from one another. Often, they serve only to construct their own isolated narrative. When the Neuaubing memorial site opens in 2025 the huge issue of civilian forced labor will finally find a proper place of remembrance. What is more, the different stories and memories of the Dutch, Ukrainians, French, Italians, and Poles as well as people from at least ten other nations will be joined up. Hopefully there will also be a cafeteria and hopefully it will serve Zuppa Romana in memory of Francesco Di Nuzzo, who every evening went to the back door of his Fontana di Trevi restaurant to give hungry Italians everything that was left over that day and who served his own dessert to Munich citizens, who ten years earlier had spat at him.

Notes from Conversations

A common thread of all our conversations with the descendants of Italian forced laborers was a sense of sadness and mourning. Not so much mourning for their dead relatives but the sadness of not knowing, of a vacuum, a feeling of emptiness. If they were able to tell us anything at all, then their stories were always about cold, hunger, scraps of food, shared rations.

Francesco Di Nuzzo (1921-1986)

Giuseppe Burani (1924-2014)

Gino De Zolt (1924-2020)

Luigi Ganora (1922-2003)

Giuseppe Degiovanni (1922-1991)

Albino Eicher Clere (1922-1987)

[1] Michele Barricelli, “Schlimmer als die beste Schilderung” – Die Erinnerung an NS-Zwangsarbeit als gesellschaftliche Aufgabe, in Winfried Nerdinger (ed.), Zwangsarbeit in München. Das Lager der Reichsbahn in Neuaubing, Berlin 2018, p. 74.

[2] François Cavanna, Das Lied der Baba. Munich/Vienna 1981, p. 267, quoted from Christine Glauning, Mittdendrin und außen vor: Zwangsarbeit in der NS-Gesellschaft, in Winfried Nerdinger (ed.), Zwangsarbeit in München. Das Lager der Reichsbahn in Neuaubing. Berlin 2018, pp. 12–27, here: p. 15.

[3] See Gabriele Hammermann, Introduction, in idem (ed.), Zeugnisse der Gefangenschaft. Aus Tagebüchern und Erinnerungen italienischer Militärinternierter in Deutschland 1943–1945, Berlin/Munich/Boston 2014, p. 10.

[4] Joseph Goebbels, Die Tagebücher von Joseph Goebbels, Eintrag 20.9.1943 sowie 23.9.1943, quoted from Introduction, in idem (ed.), Zeugnisse der Gefangenschaft. Aus Tagebüchern und Erinnerungen italienischer Militärinternierter in Deutschland 1943–1945, Berlin/Munich/Boston 2014, p. 6.

[5] Gabriele Hammermann, Introduction, in idem (ed.), Zeugnisse der Gefangenschaft. Aus Tagebüchern und Erinnerungen italienischer Militärinternierter in Deutschland 1943–1945, Berlin/Munich/Bosten 2014, p. 15.